Nietzsche wrote somewhere:

‘How differently the Greeks must have viewed their natural world, since their eyes were blind to blue and green, and they would see instead of the former a deeper brown, and yellow instead of the latter (and for instance they also would use the same word for the colour of dark hair, that of the corn-flower, and that of the southern sea; and again, they would employ exactly the same word for the colour of the greenest plants and of the human skin, of honey and of the yellow resins: so that their greatest painters reproduced the world they lived in only in black, white, red, and yellow).’

Weird, if correct. But it explains the ‘wine-dark sea’ I guess? But maybe not:

‘Today, no one thinks that there has been a stage in the history of humanity when some colours were ‘not yet’ being perceived. But thanks to our modern ‘anthropological gaze’ it is accepted that every culture has its own way of naming and categorising colours. This is not due to varying anatomical structures of the human eye, but to the fact that different ocular areas are stimulated, which triggers different emotional responses, all according to different cultural contexts.’

— Can we hope to understand how the Greeks saw their world?

New York Dropped Dead, and Some People Loved It

And the many who buy and sell people, believing everyone can be bought, don’t recognize themselves here.

Not their music. The long melody that remains itself in all its transformations, sometimes glittering and tender, sometimes harsh and strong, snail trails and steel wire.

The first configuration is what I came to call the Vampires’ Castle. The Vampires’ Castle specialises in propagating guilt. It is driven by a priest’s desire to excommunicate and condemn, an academic-pedant’s desire to be the first to be seen to spot a mistake, and a hipster’s desire to be one of the in-crowd. The danger in attacking the Vampires’ Castle is that it can look as if – and it will do everything it can to reinforce this thought – that one is also attacking the struggles against racism, sexism, heterosexism. But, far from being the only legitimate expression of such struggles, the Vampires’ Castle is best understood as a bourgeois-liberal perversion and appropriation of the energy of these movements. The Vampires’ Castle was born the moment when the struggle not to be defined by identitarian categories became the quest to have ‘identities’ recognised by a bourgeois big Other.

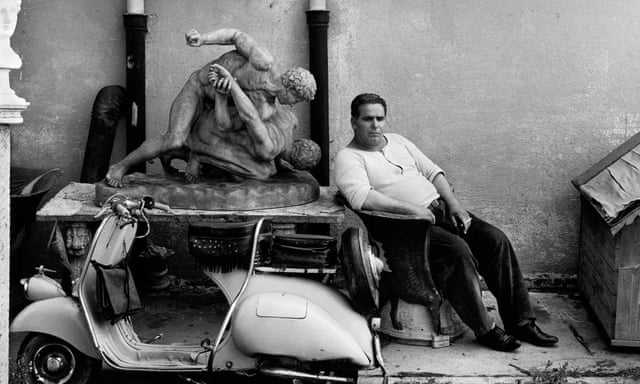

Ansel Adams once said:

‘But I would never apologize for photographing rocks. Rocks can be very beautiful. But, yes, people have asked why I don’t put people into my pictures of the natural scene. I respond, “There are always two people in every picture: the photographer and the viewer.” That usually doesn’t go over at all.’

Which is — actually — quite profound, once you think about it. Did old Ansel read up on contemporary French thought or something?

Not much of a photo, I know — but I shot it, and a few more.

Haggis pakora is a Scottish snack food that combines traditional Scottish haggis ingredients with the spices, batter and preparation method of Indian and Pakistani pakoras. It has become a popular food in Indian and Pakistani restaurants in Scotland, and is also available in prepared form in supermarkets.

Sounds … interesting, does it not?

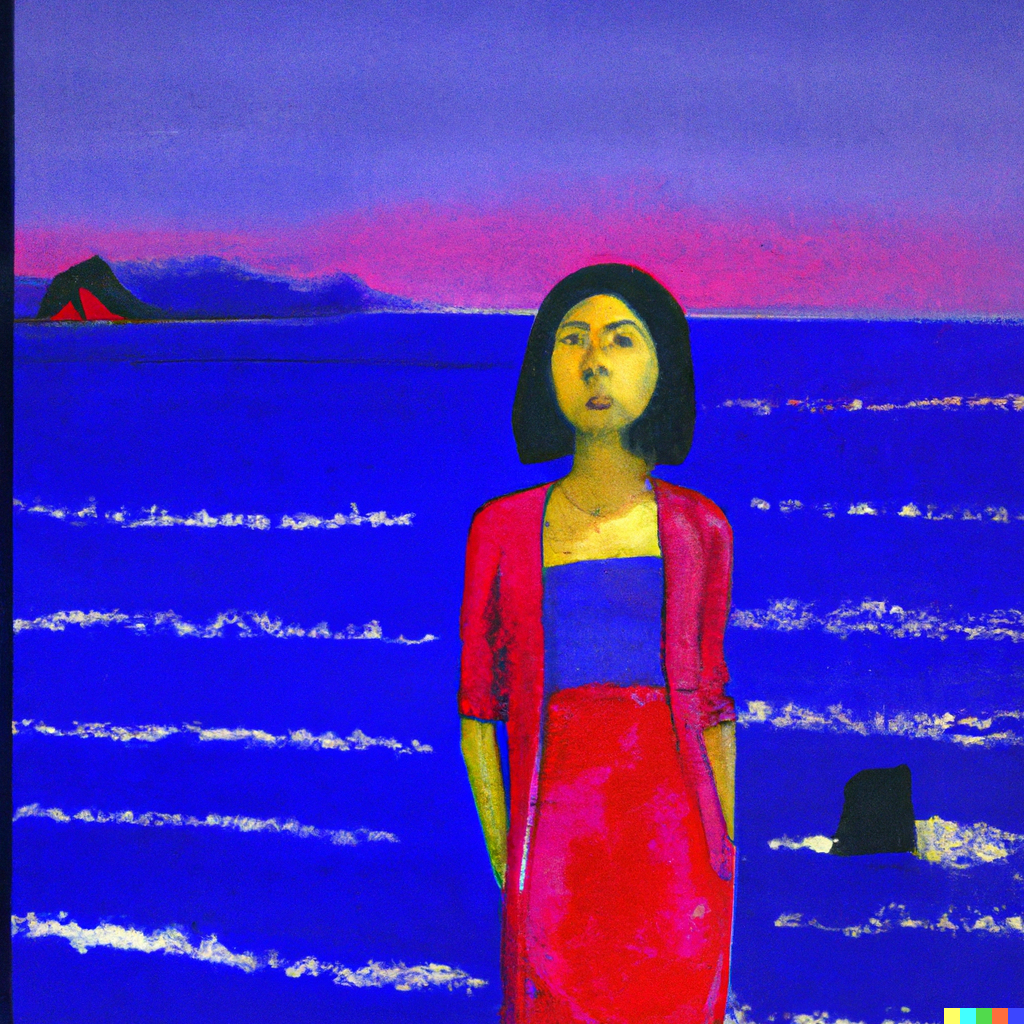

Am I the artist?

Or is DALL·E?

But realistically, the term is more likely to validate managers who think that their employees are slackers than to help ordinary workers reclaim their soul. The sheer number of quiet-quitting articles from the perspective of bosses in The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg strongly suggests that the term is current among managers too. It offers a convenient explanation for ostensibly lazy workers. Complex questions such as “Am I running my team effectively?” and “Is hybrid work actually working out for us?” can be reduced to the confident diagnosis that young people just don’t want to work.

Nothing that was not already said by, say, Paul Lafargue. We owe our bosses nothing.

‘While being translated might be a small victory for a writer working in English, it is a kind of consecration for a writer from the Global South. The market for foreign works is so slim that what gets translated is usually tailored to a particular kind of American reader — one who reaches for Latin American literature to encounter difference, or maybe to feel morally righteous for reading about the misfortunes wrought by an American government she doesn’t support. Such a reader is not looking for “universal” subjects, but for “authentic” representations of poverty, cartels, and border crossings. As a result, Latin American writers find themselves straining to cater to demand — putting on the poncho, adjusting the sombrero, and talking about the agrarian revolution or the narcos, as Mona puts it. Throughout its history, Latin American literature has been molded by translation, marketing, and distribution in the U.S. and Europe. Its waves of popularity in the mid-20th century crystallized a logic that persists today: Latin American literature can be popular overseas, but only if it closely tracks how an American reader sees, or does not see, the region’s political significance.’

I, myself, giggled a bit years ago when a Danish music reviewer threw a hissy fit over an Indonesian heavy metal band. The nerve: don’t they know it is only to be gamelan for them, for ever?

‘“A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It’s where the rich use public transportation,” says Colombian politician Gustavo Petro. His quote rings especially true when considering Tokyo’s trains. Its rail system is an equalizer between rich and poor. It’s usually the fastest way to get from A to B within the city, it’s affordable and everyone uses it. There is no stigma attached to riding the train, it’s simply the standard.’

‘It is also November. The noons are more laconic and the sunsets sterner… November always seemed to me the Norway of the year.’

— Emily Dickinson to E.H, 1865

London, probably 1978 (I remember a lot of regal souvenirs being sold). Rain, lots of rain. We stayed where we could afford it: a run-down hostel in Earls’s Court. Most of the other guests were, we found out, there for the long run. Eating in an all-you-can-eat pizzeria somewhere near Chelsea (before Chelsea became the current Chelsea). But buying records up and down Tottenham Court Road. Gawked at the punks: there was not a lot of them, but we had not seen that kind of thing back home, yet. I did see a girl with spiky black hair and weird piercings that fall, right here in Copenhagen. London before Cool Brittania. The homeless sleeping in doorways around Piccadilly Square (but perhaps they still do?) Gray and wet, closer to the postwar years than to the glitter that finance capital brought later. And now this book that I should probably buy: Souvenir.

‘Rien faire comme une bête, lying on the water and look peacefully into the heavens, “being, nothing else, without any further determination and fulfillment” might step in place of process, doing, fulfilling, and so truly deliver the promise of dialectical logic, of culminating in its origin. None of the abstract concepts comes closer to the fulfilled utopia than that of eternal peace.’

‘Less often remarked upon, however, is the fact that Sebald’s books are virtually impossible to remember precisely, which is only an apparent paradox given that the main theme in his work is memory.’

— Near-Coincidences: Digression and the Literature of the Age of the Internet

Try to praise the mutilated world.

Remember June’s long days,

and wild strawberries, drops of rosé wine.

The nettles that methodically overgrown

the abandoned homesteads of exiles.

You must praise the mutilated world.

You watched the stylish yachts and ships;

one of them had a long trip ahead of it,

while salty oblivion awaited others.

You’ve seen the refugees going nowhere,

you’ve heard the executioners sing joyfully.

You should praise the mutilated world.

Remember the moments when we were together

in a white room and the curtain fluttered.

Return in thought to the concert where music flared.

You gathered acorns in the park in autumn

and leaves eddied over the earth’s scars.

Praise the mutilated world

and the gray feather a thrush lost,

and the gentle light that strays and vanishes

and returns.

‘To be modern is to find ourselves in an environment that promises us adventure, power, joy, growth, transformation of ourselves and the world – and at the same time that threatens to destroy everything we have, everything we know, everything we are.’

— Marshall Berman

‘We could call this strange geography created by technology “AirSpace.” It’s the realm of coffee shops, bars, startup offices, and co-live / work spaces that share the same hallmarks everywhere you go: a profusion of symbols of comfort and quality, at least to a certain connoisseurial mindset. Minimalist furniture. Craft beer and avocado toast. Reclaimed wood. Industrial lighting. Cortados. Fast internet. The homogeneity of these spaces means that traveling between them is frictionless, a value that Silicon Valley prizes and cultural influencers like Schwarzmann take advantage of. Changing places can be as painless as reloading a website. You might not even realize you’re not where you started.’

‘The most tragic form of loss isn’t the loss of security; it’s the loss of the capacity to imagine that things could be different.’

— Ernst Bloch

© Henning Bertram 2025